Author Archives: Charlene Cebulski

I Think I Want A Pond…

I Think I Want A Pond…

I really believe it is hard-wired into our brains. There is something about the sound of rapidly moving water that strikes a chord in the deepest parts of our souls. Perhaps it is the (barely) upright ape in us that links that sound with basic survival, a promise of life, coolness on a hot day, and the chance, if we are quick and lucky, of dinner.

Whatever the reason, the desire to have moving water in your immediate living space has hit, and you are beginning to do the research. As you start, there are some questions you should ask.

1) How much time do I want to spend?

This question has implications both as you start up and as you persist in the hobby. If you are not careful, water gardening can easily absorb large portions of your limited leisure time and has the tendency to eat other hobbies if not closely supervised. Folks with two jobs, a young family, housework and a host of social obligations should be very careful here, and limit themselves to a pot garden at most. Those with an aversion to muck and wet should stop reading now and take up knitting. Model railroaders had better have finished work on their layouts and rolling stock, because this hobby is addictive, and their current setup will be their last, unless they can transfer their affections from HO scale to Garden Railway.

2) How much money do I want to spend?

No question here. The bigger it is, the more it costs to build and maintain.

3) How much space do I have?

This is a no-brainer if you live on the 73rd floor of a high-rise in downtown anywhere. You are only at risk if you have enough grass to mow in a protected area around your house. If you have enough grass to require a power mower, you are really in trouble. Rider mower? Uh-oh. Full-time groundskeeper and staff? Oh dear oh dear oh dear.

4) What do I want this water feature to do?

Is it just the sound of moving water you want? Do plants figure into the concept? What about animal life? Fish? Frogs? Possums? Raccoons? Deer? Herons? Neighbors? Building inspectors? Ordinance Control? If you want fish, what kind of fish are you thinking about? Goldfish are small, practically bombproof and easy on the ecology, but are considered by practically every backyard predator to be delicious and easily caught. Koi are big, beautiful and impressive, but also expensive, demanding and sometimes challenging to maintain.

How much time do I want to spend?

This question has implications in both the construction and maintenance phases of pond ownership. In construction, the obvious conclusion is that if you buy something that comes out of the box, fits on a tabletop and plugs into the wall, it’ll have instructions that say “Just add water”. You’ll end up with something that may look nice and goes “burble” (and occasionally “bing”), and won’t take up much of your time at all. It will, however tend to get ignored over time, run dry and burn out. These mini-features come under the “funny once” category of water gardening, and if they support wildlife, it wasn’t the wildlife you were thinking of.

If you are looking for an outdoor feature, but are both time and space-challenged, (Over-employed high-rise dwellers come to mind here.) a satisfactory compromise can be attained with a barrel garden. Half-whiskey barrels and convincing plastic look-alikes can be had at most garden centers, and liners for the wood barrels are also easily found. A small pump and fountain (or falls) arrangement, some rocks and small aquatic plants and even a goldfish or two complete what can be a very satisfying and relatively low-maintenance water feature.

Any advance beyond this point suggests outdoor yard space and a larger commitment of construction and maintenance time. Now is the time to stop, think and decide just what it is that you want this water feature to do.

Decision point one: “I don’t want to deal with critters, I just like the sound of splashing water. I think waterfalls are neat.”

The neatest solution to this situation is an arrangement I saw at the Midwest Pond and Koi Society’s trade show last fall (2004). It combined a liner-based waterfall of the “build-it-yourself” type, cascading down into a bed of coarse rock. This can obviously be anything from limestone landscape rock to carefully hand-chosen Wisconsin cobble rocks. The secret to the arrangement is that the waterfall cascades onto the rocks, which are contained by a large heavy-gauge plastic basin. At the bottom of this basin (about two to three feet deep) is a high-efficiency submersible pump protected by a cover. The basin is buried to its edge below the falls and filled almost to the brim with water, the level stopping just below the top of the rocks. Water cycling over the falls empties into the rocks and vanishes, to be pumped back up to the top of the falls. No open water, no mosquitoes, but plenty of places to stick plants between the rocks, and lots of room for creative rock arrangement in a small space. The small footprint of the feature keeps the amount of digging to a minimum and the major investment of time will be in arranging your waterfall rocks on the liner. Most of your ongoing maintenance time will be directed at maintaining your water level so your pump does not run dry, and fall drainage to prevent water freezing in your pump and water lines.

The key thing to remember here is that you will be digging a hole in your yard of significant depth and width. Even though it will present zero drowning risk to even the clumsiest of neighborhood drunks, it still puts underground structures in the way of your shovel. Call your local Utilities Tracking Service (in the Chicago metropolitan area it is called “Julie”). They will come out, and at no charge, will mark off where all the buried water, gas and electrical lines run. Do this first before beginning any dig.

Decision point two: “I don’t have a lot of time or space, but I’d like something pretty, with fish.”

Check with “Julie” first. Then touch base with your municipality, if you have one. Owners of farms and other rural properties do not have this issue. Most urban and suburban communities have very specific ordinances governing placement, depth and protection of in-ground water features. Many also require building permits. It is much easier on everybody if these details are dealt with before the first shovelful of earth is moved.

The decision to add fish to a water feature puts you into a whole new category of this hobby. Although shallow versions of this type of pond (18 inches or less in depth) are considered by most communities to be “water features” not requiring extraordinary protective measures, the livestock have needs that must be met, and the open water that this feature contains will also require maintenance.

To be very basic, fish eat and excrete. The products that they excrete are toxic to them, and if not disposed of in some way, will eventually kill them. In the wild, fish live in large bodies of water fed constantly by springs, streams or rivers. There are thousands of gallons of water available for each fish present. Your backyard pond offers no such luxury. Most “beginner” ponds range between 50 to 250 gallons (especially if they are of the preformed “dig and go” type) and are closed, recirculating systems. Maintenance of water quality adequate to sustain fish health will require either daily large-volume water changes or some form of biofiltration.

Very simply put, a biofilter is just a box full of something with a large amount of surface area (media) that beneficial bacteria can attach to and do their job. Water from the pond flows through it and the bacteria on the media convert the toxic ammonia produced by the fish to nitrite (also toxic) and then to nitrate (relatively nontoxic, but great fertilizer). Most biofilters also contain mechanical filters (brushes, mats, fine gravel or sand) which remove larger solid waste and floating debris. These can be home-built using food-grade plastic drums or garbage cans as the container, or bought complete with all sorts of horns and whistles from any number of manufacturers. If there is a caution to be raised with regard to any of these manufactured products, it is that the manufacturer will always overstate the filtering capacity of his product. View any statement on the box such as “…for ponds up to xxx gallons” with the gravest suspicion, and divide the “xxx” by at least 2.

Remember also that municipal water is treated to kill bacterial contaminants, usually with chlorine, chloramines or both. While these render the water safe for you to drink, they also will kill off your biological filter and injure your fish’s gills. Any pond with fish and filled from the garden tap will need to be pre-treated with a good dechlorinator.

The decision point “pretty” also implies plants. Aquatic and marginal plants are an essential part of the backyard pond ecosystem, adding shade, cover and beauty to the mix. They also provide a small amount of biofiltration, and will be important in removing ammonia from the water. Ammonia is toxic to fish and creates another problem: algae. Hobbyists deal with both floating algae and hair (or string) algae every season as a matter of course. Both are present everywhere in the pond environment, and grow rapidly in the presence of sunlight and food (ammonia-otherwise known as “fertilizer”). Growth of both types of algae can be limited by the presence of actively growing aquatic and marginal plants, but small ponds can’t support a large enough plant population to do the job and still leave room for the fish. In the case of floating algae, the kind that turns your pond to “pea soup” in late spring, the easiest solution is an ultraviolet light unit placed in your water line between your filter and your inlet to the pond. String algae is another issue, and is dealt with elsewhere.

The most basic, cheapest and easiest to install in-ground ponds are the so-called “pre-formed” type. You can see these for sale at any home and garden outlet. They have the advantage of being easy to install and run, requiring a minimum of digging or piping. They are frequently sold as kits, and may include a pump, a fountain or falls arrangement, and occasionally even a filter. From a time and money standpoint, they are very attractive.

These rarely exceed 200 gallons in capacity and have a number of drawbacks.

• They come in a limited number of shapes and sizes. This limits your ability to fit it into your landscape plan.

• The kits are usually under-filtered, and will support only small populations of aquatic life.

• The pumps are frequently designed to run small fountains and often do not move adequate volumes of water through the filter to allow for proper bioconversion. They also tend to be fairly flimsy, jam easily, and rarely last more than one season. They are inevitably submersible pumps, which present a constant maintenance problem as well, requiring that you pull them out almost daily to clear the inlets.

• They are necessarily shallow, rarely exceeding 18 inches in depth. This makes them easy targets for predators. Raccoons, possums, herons, bullfrogs and other common predators all love these types of ponds. The fish in them tend to be slow and delicious, and tend to come towards any disturbance in the water, hoping to be fed. It’s better than McDonald’s!

• The small size of these units limits your options with regard to fish. Goldfish do well. Anything bigger, such as koi, will suffer and die.

More time on the install, but…

For all practical purposes, flexible liner-based ponds are the most adaptable and most easily maintained ponds going. They can be designed to fit into any space, incorporate any feature you want, go to any depth, and if designed with forethought, can be easy to maintain, durable and almost self-sustaining from an ecological standpoint. A wide variety of liner materials are now available ranging from the old reliable (but heavy) butyl rubber to lighter, thinner and very durable space-age plastics and polymers. Since the design and building of this type of pond is entirely your choice, it allows for absolute freedom in your choice of pumps, streams, waterfalls, fountains and filters. For specifics, we refer you to Mike White’s excellent series of articles on pond construction elsewhere on this site.

How much money do I want to spend?

The fact that you are even reading this article implies that you are willing to spend something. How much you will actually unpocket will depend on your imagination, resourcefulness, energy, and the intensity with which this hobby will bite you. At the point at which it transmutes from an interest to a hobby, you begin to spend money. When it goes from hobby to enthusiasm, you can multiply your willingness to spend by a factor of at least five. When you slide from enthusiasm to obsession and become “koi kichi” and your spouse or S.O. is ready to drown you in your ever-expanding construct, you’ll need a lotto hit or two or three new jobs.

The Ebeneezer Scrooge Option

Get a pot out of your cupboard, put a piece of celery, some water, and that hokey plastic goldfish you picked up at that garage sale into it. Done.

One Notch Up

Container water gardening is a popular low-cost and space-thrifty option to ponding that allows cliff and bungalow-dwellers access to at least some of the fun of ponding. While these systems do not have the volume necessary to support koi, they will handle a couple of goldfish and a surprising variety of aquatic plant life for minimal cost. What is essential here is a small but durable pump arrangement with enough output to keep the water in the container circulating briskly. Aeration can be supplied either by a small but turbulent stream bed or an aquarium-grade air pump and stone. These tend to be inexpensive, and your container can be anything that’ll hold water and won’t leak, tip or go crashing through your floorboards. Careful attention to water quality is essential here. The major failing that these systems have is chronic under-filtration.

…and Another Notch!

Preformed ponds can be had at almost any garden supply place these days, and, if cleverly installed, can look quite good. They tend to range between 75 and 200 gallon capacity and rarely exceed 18 inches in depth. They are easy to install, and many come as kits with pump and small biofilter included. Be cautious about these systems. The manufacturer almost always overestimates the capacity of the system to support aquatic life, and even a couple of enthusiastic goldfish can overpower the filter in a couple of spawnings. These systems also are not sufficient to support koi, and worse, are very difficult to defend from predation. Raccoons love them, especially if they have (as most do) plant shelves. They knock the plants into the pond, hunker down on the comfy seat thus provided, and chow down on your fish. Possums and wading birds are also a threat, and the more rural you live, the worse the problem will be.

…One Notch Further…

Liner-based ponds can be any size, shape and depth, and if you are willing to do the work of planning, digging and piping yourself, they can be built for surprisingly little money. An article in Koi USA about three years ago detailed a complete construction plan for a liner pond, including a home-built skimmer, falls and barrel biofilter which cost, at that time, about $1200. Given the design and materials, this cost has not escalated much over the intervening years. As you get into the 800-2000 gallon range, koi keeping becomes possible, and the deeper you go, the better koi will like it. Most experienced hobbyists consider a depth of four feet to be a minimum, and prefer six to eight feet if they are planning on having really big fish. Oddly enough, maintenance and running costs decrease as the pond becomes deeper and larger, mostly due to increasing stability of pond chemistry and temperature. A well-designed deep pond is also much easier to defend against predation. Raccoons can’t fish when they’re dogpaddling, and herons can’t hunt when there is no place for them to wade.

It’s important to remember, however, that your community may have views about your project, and have probably backed them up with ordinances. These are probably easily viewed at the Public Works Office in your local Town Hall, filed under “Stuff” beneath a pile of 1944 calendars in the bottom drawer of a file cabinet in a small alcove in the fourth sub-sub-basement with a sign on the door that says “Beware of the Leopard”. As hard as it may be, staying in compliance with your local rules and regulations from the beginning saves time, energy and heartbreak later on. Remember to call your local Utilities Tracking Service BEFORE you dig. Hitting the neighborhood’s 220-volt service line with your shovel while standing in damp soil is no fun.

Doing the digging, wiring and piping yourself cuts way down on the cost, but remember, all that dirt has to go somewhere, and dug dirt takes up a lot more room than the hole from whence it came. You can use some of it to construct the hill that your stream and falls will cascade down, but neighbors tend to get cranky when the grade level of their veggie garden mysteriously rises two feet in one night. Time to cultivate that “innocent” look. (Mike White’s articles on pond building become required reading about here.)

Bam!

At the high end of this scale is the option of having a professional with heavy digging equipment and a horde of manpower come in and do the gruntwork for you. What becomes important here is in the selection of this kind of help. Ask around at other ponds about the contractors in your area. Many landscapers will offer to dig for you, but if they do not have actual ponding experience, they will screw it up and you will inevitably be disappointed, left with an unworkable, badly designed hole in the ground and no recourse and backup. Your contractor should have experience in pond construction and be willing to give you addresses and phone numbers of prior customers. He should be willing to help you design and build the pond that you want, and not a “cookie cutter” design that happens to be easy for him. He should be familiar with piping and filtration systems, or should know someone who is.

Don’t talk to just one contractor. Get multiple bids and multiple plans. Above all, talk to other water gardeners. Be sure you know what you want your pond to be and to do before you dig. A plant and frog fancier will not be happy with an 8 foot deep formal koi pond, and a certifiably koi-kichi enthusiast can’t use a winding 18-inch deep stream for anything other than eye candy.

If you are going this route, you should be thinking of volumes of 4000 gallons and up, and be planning on spending at least $7000 not counting pumps and filtration. As with any project of this magnitude, there is no upper limit on what it is possible to spend. The best local example of this exists (beautifully!) in a northern suburb of Chicago, where a hobbyist doubled the square footage of his already large and gracious home with a very deep, very large and very well-filtered indoor pond. He takes every advantage of this and scubas with his fish frequently.

I’m a Ponder!

I’m a Ponder!

I’m rough an’ tough and smarter than any fish! Why do I need to pay some club a buncha money to do this hobby? I’m just fine on my own, right?

Well, probably wrong, and for a large number of very good reasons. Beginning ponders almost always approach the hobby with a significant knowledge deficit, having either been told by the contractor that their spiffy new ponds were “maintenance-free”, or having started off with a self-dug pond with limited or absent filtration. Poor water quality and overstocking are the twin curses of inexperience, and are the most common reasons that many beginners never get past their second season as a water gardener.

Ponding is one of those avocations that, like model railroading, is a lot more complex than it looks on the surface. Water quality, filtration, circulation, water testing, planting, stocking, fish health, management of predation, injury, and disease and multiple other interrelated issues all contribute to making ponding one of the most absorbing and challenging hobbies around. It also provides the opportunity for endless disaster for the unwary.

The most effective way to avoid the common (and uncommon) pitfalls inherent in ponding is to find a bunch of experienced hobbyists and learn from them. The most common attribute of any avid ponder is his or her willingness to discuss (at length) every mistake, disaster and goof they’ve ever committed, and then share their rescues, miracles and solutions. Avid ponders are terminal fidgets, always experimenting and changing their ponds, their filters and their fish. The more of these people that a beginner can interact with, the fewer mistakes he’ll make with his own pond.

Hobbyists of any persuasion instinctively band together, and ponders are no exception. Koi and water gardening clubs abound just about anywhere the combination of fish, water and plants are possible. At any given club meeting, a beginning ponder can find upwards of a thousand man-years (or more!) of hard-won ponding experience. Presentation of a problem will result in not just a solution, but very likely many possible solutions, all of which have worked in one situation or another.

Koi societies, water gardening associations, goldfish clubs are vast repositories of knowledge and experience, and are powerful teaching organizations. If you are fascinated by this hobby in any of its many facets, you need to join a club. It’ll keep you from making serious mistakes, regardless of your level of experience, and help bail you out when you stumble over the inevitable barriers produced by Ma Nature and Murphy (the Imp of the Perverse).

Bob Passovoy

President

MPKS

Spring and Your Pond

Understanding Nitrogen and Cold Water

Spring marks the transition of our ponds from a dormant ecosystem with torpid fish and inactive filters to the active biome that we enjoy throughout the summer. This transition is a stressful one for our fish, and if mismanaged, can result in increased stress, illness and death.

Perhaps the most complex changes that occur during spring wakeup are those involving the nitrifying process that converts ammonia into nitrite, then into nitrates. Most of us are aware of this process, and if we have been paying attention to our ponds as they warm up, are familiar with the spring “ammonia spike” and “nitrite spike” that occur as our fish wake up and begin to eat, followed slowly by the development of our bioconverters as the mix of aerobic and anaerobic nitrifying bacteria come online.

Ammonia is measured by most common test kits as Total Ammonia Nitrogen (TAN) which combines both ionized and non-ionized ammonia. It is the non-ionized (NH3) form of ammonia that is most toxic to our fish, and its presence as a component of TAN increases as the water becomes more alkaline (higher pH). Ionized ammonia (NH4) is considerably less toxic, and will increase as pH drops.

It is this phenomenon that protects fish that have been held in transport bags for long periods of time, and the main reason why we never pour fresh water into that bag. Water temperature also determines (in part) the ratio of ionized to unionized ammonia, with colder temperatures favoring the presence of the less toxic ionized form.

Since unionized ammonia (UIA) becomes toxic enough to stress our fish at concentrations as low as 0.05mg/L and becomes lethal at 2.0mg/L, it becomes important to be able to separate the UIA level from the TAN as our ponds warm up in order to keep our water quality and fish health optimal throughout spring startup.

The following table, borrowed from a recent KHA course prepared by Richard E. Carlson, outlines the relationship between TAN, pH, temperature and UIA.

| TAN Level (mg/L) | Water Temp (F) | Water pH | Factor | UIA (NH3) (mg/L) | * The “Factor” column of the chart provides a multiplier derived from a number of sources, including the University of Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 0.5 0.5 |

50 72 86 |

7 7 7 |

0.0018 0.0046 0.0080 |

0.0009 0.0023 0.0040 |

| 0.5 0.5 0.5 |

50 72 86 |

8 8 8 |

0.0182 0.0743 |

0.0091 0.0219 0.0372 |

| 0.5 0.5 0.5 |

50 72 86 |

8.6 8.6 8.6 |

0.0688 0.1541 0.2422 |

0.0344 0.0771 0.1211 |

To use the chart, multiply the conversion factor closest to the combination of pH and temperature by your measured TAN. This will yield a rough estimate of UIA. Remember that toxic levels of UIA are anything above 0.05mg/l, so a combination of Total Ammonia Nitrogen (NH3/NH4) of 1.0mg/dl at a temperature of 72 and a pH of 8.6 would have an estimated NH3 concentration of 0.1541mg/l, easily enough to stress and possibly kill a pond full of koi.

Low temperatures are protective, but the ability to separate out toxic from non-toxic nitrogen levels as the pond warms up can head off trouble.

©2006 Robert D. Passovoy, MD

O Noes! More Salts!

Salt? Again? Do we use it or not, and if we do, what for? What we think about salt in our ponds changes as we talk to different experts in the field of aquaculture, and some of the finest arguments I’ve gotten into lately seem to have salt at their origins. There is no question that the versatile compound of a poisonous gas and a toxic and explosive metal has a place in the management of our ponds, and it is time once again to review its current place in our ponds.

A healthy koi does not need salt. Neither does a healthy pond. Koi are carp and carp are fresh-water fish. Their physiology allows them to pump free water out of their tissues back into their environment and maintain very much the same tissue concentrations of salt and water that all living creatures on this planet enjoy. To do this, they expend energy, and being cold-blooded and dependent on the water temperature around them to determine how fast their metabolism turns over, that energy budget is limited. That being said, salt has been shown to be helpful in the management of stressed and injured fish, presumably by lessening the osmotic difference between the inside of the fish and the outside environment, allowing the fish to clear more free water with less energy expenditure. This may allow more of the available energy to be devoted to the koi’s immune response to infection or parasitic infestation, or to devote to wound healing. Ulcers may also be helped with salt, since they represent a hole in the barrier between the inside and outside of the fish. A healthy koi uses its skin, scales and slime coat to keep free water out, and that protection is lost when an ulcer forms. Salt in the water reduces the free water diffusing through the ulcer and in turn reduces the amount of water the fish has to pump back out.

How much to use is open to argument, and you’ll get a different answer from every expert you talk to. The numbers you hear the most range from 0.15 to 0.3 per cent salt, with some advisors going as high as 0.6 per- cent in isolation tanks for very sick fish. Concentrations as high as 2 lb of salt in 10 gallons of water are frequently used as a dip to terminally discourage parasites.

An extensive online search on the subject proved interesting. Google Scholar yielded 133,000 articles incorporating pond and salt. None of them were in any way related to backyard koi ponds and most of them dealt with construction and maintenance of power-generation from non-convecting salt ponds. Narrowing down to keywords “Koi, salt” got me 22,000 articles, only one or two on subject. Those from actual scientists dealt mostly with using high-concentration salt baths as a dip or disinfectant. The only mentions of salt use in ponds fell into three categories. The first set dated from my last search about three years ago and centered around a series of articles by Brett Fogle, who runs MacArthur Water Gardens, an online commercial operation that sells (you guessed!) pond salt. He was all for constant and consistent use. Interestingly, newer articles and posts from him have changed their tone, and he’s a lot less enthusiastic about it now. The second set represented the majority opinion in the articles, posts and blogs that I sampled. Salt is useful as an anti-parasitic dip and an early spring treatment for protection against high nitrite levels. It is NOT recommended for constant treatment in the pond. The third set recommended avoidance of the chemical entirely, except as a high-concentration dip for transported fish, or fish fresh out of the mud pond, the sudden osmotic stress serving to explode most of the parasitic load on a fish on contact. It was interesting to note that the geographical locations of these sources were generally places that did not experience winter.

Salt’s ability to kill parasites is problematic. Epistylis, Trichodina and Ichyophthirius (Ich) will be inhibited (but not eradicated) at concentrations of 0.3% and this effect is often temporary. Fish with leeches, Anchor worms and Costia require individual dipping in 2% salt baths as well as 0.3% concentrations in the pond water, though repeated or extended exposure to salt tends to generate tolerance and resistance to treatment. Dactylogyrus and Gyrodactylus (gill and skin flukes) laugh at salt (a sniggering Dactylogyrus is a nasty thing indeed) and many of the effective treatments require low or zero salt concentrations to limit toxicity.

There is no question in anybody’s mind that salt is vital in early spring. As the populations of nitrifying bacteria wake up and start the conversion of ammonia to nitrite to nitrate, it rapidly becomes clear that the crew that handles ammonia-to-nitrite are the cheerful early risers, while the nitrite-to-nitrate gang seems to need several cups of strong coffee and a couple of extra weeks to get going. During that high-risk period, salt provides protective chloride ion to compete with the nitrite in the fish’s blood. The necessary 30:1 ratio of chloride to nitrite is easily supplied by a 0.2% salt concentration, maintained until nitrite levels drop to zero.

Frequent water changes and very limited feeding will help keep the problem under control.

Okay. If you are going to use salt, it is critically important that you know how to manage it. There are RULES.

Rule 1: Salt in your pond is there forever. If you have evaporative losses, the concentration goes up. The only way to get rid of it is to do water changes. Many, many water changes.

Rule 2: Salt kills plants. Sometimes this is a good thing. Salt in the pond in early spring can limit algae blooms, although it won’t eliminate them entirely. Concentrations higher than 0.2% will wipe out your tender aquatics and keep your water lilies from thriving. Watering your garden with salted pond water gets you the Sahara desert.

Rule 3: You must know how much salt you have in your pond. At all times. This means you need a reliable test kit or a meter. These are widely available and will generally report levels in either % or parts per thousand. Any test kit that reports concentrations in “color zones” or wide ranges is not worth the money you paid for it. For reference purposes: 1 ppt = 0.1%

Rule 4: Change salt concentrations SLOWLY. This means both directions. Slow up, slow down. Bring your salt levels up gradually over a period of days to your target. Bring them down over a period of weeks with water changes.

Rule 5: Don’t leave salt in when you don’t need it. ‘Nuff said.

Rule 6: Know how much salt to add before you add it. Hence the formulas.

Rule 7: Use the right salt. 99.9% pure or “Solar Salt” or “Blue Bag” salt. NOT pelletized or water-softener or road/sidewalk salt. Pickling salt is okay but way expensive and is for pickles, not fish. Pond salt or “aquarium salt” from the pet store is a flat ripoff. Iodized salt is expensive, and the iodine will injure gill tissue, just like its near-relative, chlorine (Look two spaces down from Cl in your handy-dandy Pocket Periodic Table). What you need is available from your local Home Despot equivalent for about 4 bucks per 50 lb. bag. It is evaporated sea water and contains other minerals (magnesium, calcium and others) which will act as buffers to stabilize your pond’s pH and will also supply trace minerals essential for koi health.

The “Not Rocket Science” Formulae:

Lb salt to add = (total gallonage of your system/120) multiplied by (desired salt conc. in ppt – current salt concentration in ppt)

For example:

Pond system volume: 4400 gal

Desired salt concentration: 1.5 lbs/100 gal = 1.88 ppt

Current salt concentration = 0.6 ppt

Lbs salt needed = (4400/120) x (1.88 – 0.6)

= 36.666 x 1.28 = 46.99 lbs salt

What is ultra-cool about this formula is that you can mess with it and get a formula to estimate the gallonage of your system. This is where an accurate test kit is critical.

Total gallonage of your system = 120 x Lb salt added / the difference between the salt concentration (in ppt) before and after you added the salt

To use the formula, you need to measure the salt concentration before and after you add a known amount of salt. Remember to give the salt enough time to thoroughly disperse throughout your pond. One day is just dandy. The amount of salt you choose to add will depend on the size of your pond and the accuracy of your test kit.

For example: A new pond. Medium to kinda big size. Good salinity meter from Aquatic Eco-Systems.

Starting salt concentration: 0.2 ppt

You add: 40 lb salt

Wait one day.

Final salt concentration: 1.0 ppt

1.0 – 0.2 = 0.8 ppt

Total gallonage = 120 x 40 / 0.8 = 6000 gallons

“Not Rocket Science”: Defined as the amount of math I can do without having to take off my shoes and socks.

So, here’s my recommendations:

Use salt sparingly, just like you would any other pond additive.

Monitor levels carefully. Don’t dose too high or change too fast.

Leave it in long enough to achieve your goal, then get rid of it with water changes.

© 2013 Robert D. Passovoy, MD

A Koi Show Manual-Norm Meck Revisited

Download this article as a PDF

The ultimate goal of a water quality team at a Koi show is to return the exhibited fish to their owners in as close to the condition they were in when they were delivered. Without the advantages of some of the sophisticated “flow through” systems in use in the Pacific Northwest, made possible by cell venues that have not only excellent water supply but also extraordinarily convenient drainage, those of us here in the Midwest are thrown back on the system originally developed by Norm Meck for his spectacular shows in San Diego. The main reference for his techniques are outlined in his article January/February 1998 issue of Koi USA. Shortly after the publication of this article, Anne and I went out to San Diego and joined Norm’s water quality team. This was almost the last Japanese-style koi show held in the United States. Shortly afterward, KHV devastated the Hofstra Koi show and effectively put an end to Japanese-style shows. Norm’s article deals with the Japanese show and, to my knowledge, there have been no updates since.

This article will take the reader through the sequence of events leading up to a British-style show, then through the show prep, load-in and maintenance, all the way to check-out and delivery of the fish back to their owners.

Six months and counting:

Yeah, I know it’s freezing out there, but now is when you need to start making lists and getting your materials together. If you have decided to get a Show sponsor to help with expenses, now is when you need to be calling them. There are a load of other shows out there, and only a limited number of vendors with the resources and willingness to sponsor. Get on the computer, fire up the email and get going. If you do it right, your major chemical expenses can be next to nothing.

Go back over the records from the previous year and decide if what you had to work with was enough. Make the adjustments you need, always working with your Show Chairman, so there are no surprises. It is no fun to show up and see ten additional vats that you hadn’t planned for awaiting your attention. Don’t ask what overnight shipping on ten pounds of ClorAm-X costs. Fedex will love you. Your budget will not.

You will need:

- Enough Stress-X (or equivalent) to supply ½ cc per gallon for every vat you treat

- Enough powdered ClorAm-X (or equivalent) to treat every vat initially for 2 ppm “cushion” and additional 1 ppm doses as needed to handle the ammonia produced through the show by the fish. Depending on loading, stress levels and length of pre-show fasting, this can range from zero for a lightly loaded vat to as much as an additional 4-5 ppm for a crowded vat containing Moby Koi and her mother, Kong.

- Enough fresh salicylate-type ammonia test reagents to take you through the show. Order these to arrive 2-3 months before showtime. Use whichever brand you are most comfortable with. Mydor makes a nice, fast 2-step kit, but it has a limited shelf-life. I like LaMotte. It’s a three-step process and is a little slow, but the major vendor (Aquatic Eco-Systems) tracks the lot numbers and can give you the date of manufacture if you call them.

- Ammonia standard. You can make up your own if you can get ahold of dry ammonium chloride and a micrometer balance and do the math and… I get a standard solution of 150 mg/L ammonia from Hach in Loveland, CO. It has a five-year shelf-life and is much easier to deal with.

- A gallon jug of distilled water for rinsing tubes and pipettes, and for making up your ammoniastandard.

- Test tubes, pipettes, graduated cylinders, buckets, tube racks, disposable cups, pitchers,dishwash detergent, paper towels, markers, note pads, scales and whatever else you’ll need to doyour job.

- Your record book with enough vat spreadsheets to match the number of vats you are managing.OR an iPod with Todd Wyder’s nifty new Show Management software (currently indevelopment).

- A battery-powered drill with a beater head from the kitchen clamped into the chuck. This maybe your most important piece of equipment.

- The rest of your pond test kit.

- Your eyes, ears, nose and brain, all in full working order.

Two weeks and counting. . . .

Having gotten the final vat count from your Show Chair, it’s time to pre-measure the chemicals. The goal of the exercise is to prevent any ammonia from touching any fish. To this end, we pre-treat each vat to provide 2 ppm of absorptive power before the fish go in and test with a titration procedure through the show to track the rate at which the cushion is being depleted. Measuring out the doses at the show is impossible. You’ll need to prepare in advance.

You will need:

- The ClorAm-X you got five months ago

- Scales accurate to 0.1 mgm (electronic kitchen scales can do this!)

- Many ziplock sandwich bags

- a good dust mask (you do NOT want to breathe this stuff!)

- A free morning when you can sit outside and do this.

- Plastic cups to hold the bags on the scale

- Boxes to hold the filled bags

ClorAm-X and its new competitor ProAm-X are apparently different enough so nobody seems to be suing anybody else for patent infringement. Interestingly, they both require exactly the same dosing to neutralize the same amount of ammonia. So…

To remove 1 mg/L (1 ppm) of ammonia, 1 gram treats 8.3 gallons.

So: For a 300 gal (6 foot) vat: x grams= 300gal x 1 gram/8.3 gal= 36 grams

For a 500 gal (8 foot) vat: x grams= 500 gal x 1 gram/8.3 gal= 60.2 grams

Wearing your dust mask (you really really don’t want to breathe this stuff) weigh out, seal and store enough 2ppm bags to treat all your vats once, and enough 1ppm bags to treat all your vats 4-5 times. Do this outside on a fairly dry day. The chemical is vigorously deliquescent (look it up) and will weigh more in high humidity the longer it is exposed to the air. You won’t use them all. That’s okay. They’ll keep ’til next time you need them.

Pro-Line has had an exact duplicate of ClorAm-X for years, and it appears to have caught up with them. As of the 2016 season, the new formula smells bad, treats 1/5 less water, is more deliquescent (look it up!) and is more expensive. The smell does dissipate and the fish seem to do okay, but it is more difficult to handle in the prep phase. The numbers are as follows:

6 foot vat @ 300 gallons: 1ppm=45 grams, 3 ppm=135 grams

8 foot vat @ 500 gallons: 1ppm=75 grams, 3ppm=225 grams

If you choose to use this product, you’ll need to order 1/5 more than you were planning on.

Given the ammonia preload given us by our friends at the Metropolitan Water Reclamation Department of Metro Chicago, which ranges from 0.5ppm on a good day and up to 1ppm on a bad day, we’ve started preloading our vats @ 3ppm.

Thursday before the show:

The vats got filled yesterday. The water mopes used a sneaky device invented by Norm’s wife; a length of PVC pipe marked in 1-inch gradations. Each inch corresponds to the number of gallons in that

section of the cylinder. There are two formulas for this: Norm’s quick-and-dirty estimate, which we mostly use and which slightly overestimates the volume, or the actual math, which corresponds to SCIENCE.

Norm’s Quick-and-dirty: Diameter of the vat squared/2

6 ft vat = 6 x 6/2 = 18 gal/inch

8 ft vat = 8 x 8/2 = 32 gal/inch

The only reason this works is that the vats aren’t perfect cylinders. They bulge, and the extra volume in the bulges makes up for the short measure on the stick.

Real math: pi x radius squared x depth (one inch or .08333333 ft) x 7.45 gal/cu. ft. water

6 ft vat = 3.14 x 9 x 0.083 x 7.45 = 17.63 gal/inch

8 ft vat = 3.14 x 16 x 0.083 x 7.45 = 31.33 gal/inch

Ann Meck put t-pieces on either end of the pipe so it could be used to whap out the edges of the vats for filling. One end for 6 foot, the other for 8 foot. A marvelous tool. Go make yourself a bunch!

On arrival at the show venue, set up your gear first. Make sure you have everything you’ll need, where you need it. Then start with the vats. Bully the Show Chair into giving you at least one 6-foot vat for your use alone. No fish will ever see the inside of that vat. It will serve as your source of water for the dosing procedures during the course of the show. Keep it netted. It is yours. Get a sample from it, untreated and fresh from the source. Label it “Source water” and test it for ammonia, along with pH, alkalinity, chloramine, chlorine and pH. Get a water temperature while you are at it. You may get a nasty shock when you do. Make up an information sheet with these values and give them to everybody who has anything to do with fish, ESPECIALLY THE VENDORS!

As part of the preparation for the 2013 MPKS koi show, we pre-treated the show vats with the 2 ppm (AmQuel/ClorAm-X/ProAm-X) ammonia “cushion” recommended in the article published in the inaugural issue of Koi Keeper. As we proceeded with our routine pre-show testing, we noticed that our test runs in multiple unpopulated vats were “breaking” at tube 4, indicating that at least 1.0 ppm of our ammonia cushion was gone before any actual fish hit the water.

The water quality team discussed this and developed two hypotheses to explore:

- The water treatment we used (ProAm‐X from Pro Line) may not be binding the ammonia “instantly” asit claimed on the label and our results may reflect an inadequate “dwell time” prior to testing.

- Water treatment at the hydrant source (Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago)includes chloramine (NH4‐Cl) which preloads our source water with ammonia.

To test this, we tested source water for chloramine, finding at least 1.0 ppm of this compound in the source water. We collected samples from a random, untenanted vat and allowed the ammonia standard to dwell for 5 and 10 minutes. The results were the same in both runs, with the “break” consistently occurring at tube 3 or 4. Adding an additional 1 ppm cushion to the vat resulted in a slight break at tube 5.

This year (2014), we tested the untreated water for chlorine (0.8 ppm), chloramine (1.5 ppm). And,

using the salicylate method ammonia test kit from LaMotte, ammonia. Not surprisingly, we obtained a value of 1.5 ppm from this test.

The conclusion to be drawn here is that water pretreatment with chloramine at the municipal water source constitutes a significant pre-show ammonia load and must be measured and accounted for in your show preparation. Your vendors must also be notified of this preload so that they can pre-treat their vats appropriately and avoid losses to their stock.

Chloramine levels can vary significantly from year to year and from day to day, based on water temperature and organic load in the source water.

Two six-foot vats will be reserved for net and bowl (and hand!) disinfection. Bleach (which must be renewed each day) or benzalkonium chloride can be used as disinfectant. BK is easier on skin and is stable, but is way more expensive.

Bleach is effective at about 200ppm, or about 5 oz per 10 gallons water. This averages out to 1 gallon in 250 gallons water, renewed on each day of the show that nets and bowls are in use. This vat is clearly labeled : BLEACH!!!!. The second vat contains sodium thiosulfate at a concentration of 1 gram/10 L water (12 oz per 1000 gal or… well you do the math. You’ve got one of Ann Meck’s tools, dontcha?). This vat is labeled: RINSE!!!!!!.

If you are feeling wealthy, benzalkonium chloride (BZK) is easier on the skin and gear, is relatively koi-safe and does not have to be “boosted” every day. The rinse vat is water only. It is available in solutions of 50% strength from nationalfishpharm.com, (about $125.00 a gallon or $21 per pint). A concentration of 1000ppm is recommended for rapid disinfection. This works out to 1800cc or 60 oz (about 2 quarts) in 300 gallons water. A gallon should last you 2 shows.

Better yet, housekeeping supply companies sell “Lysol No-Rinse” disinfectant in gallon jugs for not very much money. It is a 10% solution of-you guessed it-benzalkonium chloride! 1 gallon added to 512 gallons of water makes up the 200 ppm solution we need. This concentration will disinfect a net or vat or pair of hands with about 1 minute of soaking. It’s soapy stuff. Add it to water, not the other way around. Rinse in water. Label your vats.

Vat Prep

By now, the vats should all be numbered. Make up a record for each vat, using the form on the penultimate page of this article. Take a 8-12 oz. sample from your source/reserve vat, label it “source water” and set it aside. Each vat is now pre-treated with ½ cc/gallon of Stress-X (or Novaqua), followed by 2ppm of ClorAm-X (ProAm-X). The liquid Stress-X goes in first and is recorded on each form as it goes in, along with the time and date. The powdered material must be dissolved prior to dosing, and here’s where that pitcher and power drill with the egg-beater comes in. Since there are no fish in residence, the isolation procedures you’ll use for the rest of the show aren’t necessary here. Dip out a half-pitcher of water from each vat, dump the powder into the pitcher and mix it thoroughly before dumping it back into the vat. Record this in the “Amq” (Amquel) column as “2ppm” next to your “Nova” entry as you do it. This prevents double dosing or missed vats. Collect a 12 oz sample of treated water from any vat (you treated your source vat, too!), Set it aside.

Using the form on the last page of this article, run and record the indicated tests on your untreated

source water and your vat standard. There will probably be some chlorine and/or chloramine in the untreated water unless your show is running off well water. It should not be present in the treated vat standard. There should be NO AMMONIA ANYWHERE.

Check to make sure that the air system is working well, do your dishes and call it a day.

Friday:

Start EARLY!

Your first task is to prepare your ammonia standard. The goal is to provide a single drop of standard that will create a concentration of ammonia of 0.25ppm in 5cc of distilled water. Since the surface tension of water and the force of gravity don’t vary much, most dropper bottles deliver a drop of a size such that 115 drops equals 5cc. If you can find a bottle that comes close to this, you are good to go. I found an excellent specimen in the 60 cc capacity bottle that contains the #1 Saliclyate reagent for the LaMotte Salicylate ammonia test kit. We tested this bottle repeatedly under show conditions, and it came out at 115 drops per 5 cc each time.

Given the above drop size, you’ll need 50cc of standard solution at a concentration of 29ppm.

Here’s how you get there. The math is real. We got Pat McCray to take off his backward gimmee-hat in order to generate these elegant numbers:

If your head has not yet exploded from the math, you now have your ammonia standard. Label the bottle with the exact directions for making up the standard so you NEVER HAVE TO DO THE MATH AGAIN! Now it’s time to test the standard and your ammonia test kit.

Set up 5 test tubes in one of your racks with 5cc each distilled water. In each successive tube place 0,1,2,4 and 8 drops (0,0.25,0.5,1.0 and 2.0ppm) of ammonia standard. The zero tube is always “tube 1”. The 2ppm tube is always “tube 5”. Mix. Run your ammonia test, mixing between steps. Compare with the test comparator for accuracy. If you don’t have a nice rainbow, either your standard or your test kit is bad. A full line of zero ammonia indicates a failed test kit. Other abnormalities, such as 4+ ammonia everywhere, suggests that you goofed up the prep on the standard.

At the same time, get a sample from any one of the empty vats, or from your vat standard. Set up 5 tubes containing 5 cc each. In each successive tube place 0,2,4,6 and 8 drops (0,0.5,1.0,1.5 and 2.0ppm) ammonia standard. The zero tube is always “tube 1”. The 2ppm tube is always “tube 5”. Mix. Run your ammonia test, mixing between steps. This tests your vat’s protective cushion against ammonia. You should not see any color change in any tube except possibly tube 5. This reflects a 2ppm ammonia safety margin. Remember to use the first set of tests you did with the distilled water as your comparison standard. It’ll be more accurate than the cards or slides that came with your kit.

You will be using this last titration technique over the course of the show to monitor conditions in the show vats. You will be loading a set of 5 tubes with a water sample taken from a vat with fish in it. Each vat that you test will have a cup or other suitable container labeled clearly with that vat number and it is EXCLUSIVE TO THAT VAT. The sample is taken in such away that only the cup comes in contact with the water to avoid cross-contamination.

Keep the cups at your station, re-use them as needed.

Record Keeping:

This is the central principle of this entire exercise. Anything that happens to any given vat should be recorded on the spreadsheet assigned to it. This includes titration results (specifically the tube “break” number), any chemical added to the vat with time and date, and any unusual occurrence (spawning, flashing, stress, jumping, relocation or other events) . The totals of the ClorAm-X dosing from prior shows allow you to plan for the next one. One member of your team is generally the record keeper. He or she will generally have the best idea of potentially troubled vats based on load ratios and prior dosing.

We sample one or two of the most heavily laden vats, one “mid-range” vat and at least one lightly-loaded vat at the beginning of the show. Further testing is done as needed, based on the circumstances that arise during the show. (Irritability or odd behavior, spawning events with the fish moved to a smaller vat and no longer fasting!, and like that).

What you are looking for is a break in the color along the line of tubes. Any positive test for ammonia in any tube reflects enough ammonia to overcome some of the 2ppm safety margin in the vat water.

THE GOAL IS TO PROVIDE A 1ppm SAFETY MARGIN OF AMMONIA PROTECTION IN ALL TANKS AT ALL TIMES.

Therefore:

Color “breaks” in tube 5 or 4 indicate a safety cushion of 1.5 to 2ppm ammonia. Re-treatment of these vats should not be necessary. Break in tube 3 reflects a 1.0ppm safety margin. This is still good, but if it is obtained at the end-of-day testing, it reflects a “trouble “ vat and it and all similarly and more heavily loaded vats will require supplemental treatment to restore the 2ppm “cushion”. Color breaks in tube 2 will need more aggressive repletion. You should never see ammonia in tube 1. That is a vat that has chewed its way through 2ppm of protection and there is now ammonia in with the fish. The professional term for this is “BAD JUJU”. The vat needs to be inspected for evidence of spawning, failure to fast, or simply overloading. The fish should be relocated if possible.

About the most maddening thing in the world is to be in the middle of a titration run, concentrating on your drop count, when someone comes up to your station and starts asking you questions, yelling out numbers and otherwise distracting you from your task. Prepare signage for your table indicating an immediate and ghastly demise for anyone breaking your concentration. Mine says”DO NOT SPEAK TO THE GEEK when he is counting”.The back side of the sign has short-cut charts for the titrations. Make yourself one of these, or more.

The Guests Arrive. . . .

By this time, the fish will be arriving and will be assigned to their vats, floated, benched and entered. Optimal vat loads, maximum vat loads, point scoring and load rate calculation are available on the form on the last page of this article. These values have been arrived at on the basis of a wide base of show experience at multiple shows. It seems to work better than prior estimates of vat loading from previous articles. The load ratio is a useful tool to identify those vats that are likely to use up their safety margin most rapidly, and provide a bellwether effect for similarly loaded vats. Your show staff should provide you with the number and sizes of fish in each vat. Since shows all conform to the “British Style”, no fish will be moved from its vat unless a vat is being broken down due to unusual circumstances.

As the data comes in, survey the vats, determine the load and calculate and record the load ratio for each vat. Pick out one or two heavily loaded vats, one or two mid-range and one lightly-loaded vat as your target vats.

As the data comes in, survey the vats, determine the load and calculate and record the load ratio for each vat. To do this, get a report from your benching crew as soon as they have data available and divide the total points in the vat by the OPTIMUM load for that vat. A 6-foot vat has an optimum load of 20, an 8-footer has an optimum load of 35. An optimally loaded vat will have a load ratio of 1.0 or less. Vats with ratios greater than 1.0 will need either closer monitoring, or some of the inhabitants will need to be relocated to another vat. Pick out one or two heavily loaded vats, one or two mid-range and one lightly-loaded vat as your target vats. A show venue data sheet with fish size (1 through 8) and their corresponding point loads appears at the end of this article, along with a specimen vat record.

Be aware of a significant glitch in the benching system! If your show admits longfin koi, they are all benched as a size 7 fish, no matter what size they actually are. This will register in your calculations as a severely overloaded vat, especially if the owner really likes longfins and brought 3 or for of his size 2s. (Yes, it did happen like that at the 2016 MPKS show. I’m asking to get that glitch fixed.)

A lot of what we do here seems concentrated on chemical and mathematical fiddling. If this were just SCIENCE, it’d be boring and nobody would do it. Most of what we do, however, depends on our ability to judge what the conditions in each vat are based on a number of very subjective clues. Once the vats are loaded, it is our responsibility to survey each one fairly frequently, looking at the fish for signs of stress( clamping, flashing, red fins, irritability) and at the water for signs of sloughed slime coat, poor fasting or spawning. Often, our noses are better at this than our eyes. While we’ll be routinely testing our target vats, any vat that looks “funny” will rate a test.

It’s Friday night. The vats are still fresh, everybody’s tucked in and netted. No testing yet, no re-treatment necessary. Go home.

Saturday: SHOWTIME

Get on-site at least two hours before the show opens. Uncover the vats and survey them for problems. Full quarantine procedures apply from this point on. Do not cross-contaminate. If you come in contact with water from any vat, disinfect before you approach another. Get samples in labeled cups from the target vats and set up titration runs on them.

In general, any stretch of time in excess of 8 hours will probably require a 1ppm treatment boost as a routine procedure. Plan on a 1ppm treatment for all vats every morning and at 4:00pm during the show. Additional treatments will be guided by your titrations. The exceptions will be the lightly loaded vats which may need only one or two treatments.

With fish in the vats, re-dosing with ClorAm-X changes technique. Your reserve vat now becomes your best friend. Lay out a 1ppm packet of ClorAm-X by each vat, get that drill and pitcher and a whole lot of buckets. NEVER dump the powdered product directly into the vat. The fish are fasted and hungry, and will swim directly to it and slurp it down. While it is non-toxic when dissolved, in the powdered state it is lethal. Fill your buckets from the reserve tank and fill your pitcher from the buckets. Dissolve the powder in the pitcher with the drill and disperse the solution as broadly as you can into the vat. Record each dose as “1ppm” with the date and time in the “Amq” column.

Now review your titrations. Color breaks in tubes 2 or 3 on Saturday AM indicate stressed vats and the need for increased vigilance and additional treatment. Throughout the day, continue to assess the vats, retesting as seems necessary. Stay out of the Judge’s way. Smile, answer questions, shmooze the vendors. Buy a T-shirt.

Plan on a routine ClorAm-X boost as the show closes at 4:00 PM. Testing of the lightly loaded vats may allow you to exclude them from supplementation.

Net ’em up, shut ’em down. Go to the Awards Dinner. If you are nervous about any of the vats, sneak back in to make sure everything’s okay after the Dinner before you go home. Check the air lines while you’re there.

Sunday: Maintenance and shutdown.

Get in two hours before the show opens-again. Retest your target vats and any others that look like they need it. Re-dose with 1ppm, guided by your titrations. Additional supplements as needed. Record as before.

Start packing up. You’ve been washing out your test tubes as you’ve used them, do a final “mega-wash” and pack them away. Keep an eye on the heaviest loaded vats as the show winds down. At this point, the reserve vat that supplied water for your treatments becomes transport water to get the fish home. Try to ignore the vats where those randy little @#%$$**! spawned last night.

Good job. Go home. Start working on next year’s show.

My thanks to Norm Meck, who got me hooked on this craziness. References are “A Koi Show Water Quality Perspective” by Norm Meck, Koi USA, Jan/Feb 1998 and “Disinfecting Recommendations” by Spike Cover, Koi USA, July/Aug 2003. Thanks go also to Pat McCray, an actual math professor who teaches (shudder) calculus to undergrads at IIT. He looked at my math, got a headache and, after yelling at me for a while, agreed to come up with the actual REAL MATH that you see for the calculations necessary to prepare the ammonia standard. Finally, I gotta thank my water quality team at the 20th Annual MPKS Koi Show. Bob, Pat,Todd, Scot…not survivable without your help.

RDP

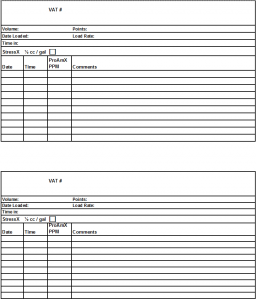

SHOW VENUE:________________________________ DATES:________________________

SOURCE WATER:_____________________________

Temp:_____________

DO:_______________

Alk:_______________

pH:_______________

Cl/Cl-NH3:______________

VAT LOADING REFERENCE

Limits:

6 foot (300 gal.):

Optimum: 20 points

Maximum: 25 points

8 foot (500 gal):

Optimum: 35 points

Maximum: 45 points

Load ratio: # points in vat (divided by)

allowable points in vat

Vat loading

| FISH SIZE | POINTS |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0.3 |

| 2 | 1.0 |

| 3 | 2.0 |

| 4 | 5.0 |

| 5 | 8.0 |

| 6 | 12.0 |

| 7 | 18.0 |

| 8 | yikes! |