Category Archives: Koi and Ponds

I’m a Ponder!

I’m a Ponder!

I’m rough an’ tough and smarter than any fish! Why do I need to pay some club a buncha money to do this hobby? I’m just fine on my own, right?

Well, probably wrong, and for a large number of very good reasons. Beginning ponders almost always approach the hobby with a significant knowledge deficit, having either been told by the contractor that their spiffy new ponds were “maintenance-free”, or having started off with a self-dug pond with limited or absent filtration. Poor water quality and overstocking are the twin curses of inexperience, and are the most common reasons that many beginners never get past their second season as a water gardener.

Ponding is one of those avocations that, like model railroading, is a lot more complex than it looks on the surface. Water quality, filtration, circulation, water testing, planting, stocking, fish health, management of predation, injury, and disease and multiple other interrelated issues all contribute to making ponding one of the most absorbing and challenging hobbies around. It also provides the opportunity for endless disaster for the unwary.

The most effective way to avoid the common (and uncommon) pitfalls inherent in ponding is to find a bunch of experienced hobbyists and learn from them. The most common attribute of any avid ponder is his or her willingness to discuss (at length) every mistake, disaster and goof they’ve ever committed, and then share their rescues, miracles and solutions. Avid ponders are terminal fidgets, always experimenting and changing their ponds, their filters and their fish. The more of these people that a beginner can interact with, the fewer mistakes he’ll make with his own pond.

Hobbyists of any persuasion instinctively band together, and ponders are no exception. Koi and water gardening clubs abound just about anywhere the combination of fish, water and plants are possible. At any given club meeting, a beginning ponder can find upwards of a thousand man-years (or more!) of hard-won ponding experience. Presentation of a problem will result in not just a solution, but very likely many possible solutions, all of which have worked in one situation or another.

Koi societies, water gardening associations, goldfish clubs are vast repositories of knowledge and experience, and are powerful teaching organizations. If you are fascinated by this hobby in any of its many facets, you need to join a club. It’ll keep you from making serious mistakes, regardless of your level of experience, and help bail you out when you stumble over the inevitable barriers produced by Ma Nature and Murphy (the Imp of the Perverse).

Bob Passovoy

President

MPKS

Spring and Your Pond

Understanding Nitrogen and Cold Water

Spring marks the transition of our ponds from a dormant ecosystem with torpid fish and inactive filters to the active biome that we enjoy throughout the summer. This transition is a stressful one for our fish, and if mismanaged, can result in increased stress, illness and death.

Perhaps the most complex changes that occur during spring wakeup are those involving the nitrifying process that converts ammonia into nitrite, then into nitrates. Most of us are aware of this process, and if we have been paying attention to our ponds as they warm up, are familiar with the spring “ammonia spike” and “nitrite spike” that occur as our fish wake up and begin to eat, followed slowly by the development of our bioconverters as the mix of aerobic and anaerobic nitrifying bacteria come online.

Ammonia is measured by most common test kits as Total Ammonia Nitrogen (TAN) which combines both ionized and non-ionized ammonia. It is the non-ionized (NH3) form of ammonia that is most toxic to our fish, and its presence as a component of TAN increases as the water becomes more alkaline (higher pH). Ionized ammonia (NH4) is considerably less toxic, and will increase as pH drops.

It is this phenomenon that protects fish that have been held in transport bags for long periods of time, and the main reason why we never pour fresh water into that bag. Water temperature also determines (in part) the ratio of ionized to unionized ammonia, with colder temperatures favoring the presence of the less toxic ionized form.

Since unionized ammonia (UIA) becomes toxic enough to stress our fish at concentrations as low as 0.05mg/L and becomes lethal at 2.0mg/L, it becomes important to be able to separate the UIA level from the TAN as our ponds warm up in order to keep our water quality and fish health optimal throughout spring startup.

The following table, borrowed from a recent KHA course prepared by Richard E. Carlson, outlines the relationship between TAN, pH, temperature and UIA.

| TAN Level (mg/L) | Water Temp (F) | Water pH | Factor | UIA (NH3) (mg/L) | * The “Factor” column of the chart provides a multiplier derived from a number of sources, including the University of Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 0.5 0.5 |

50 72 86 |

7 7 7 |

0.0018 0.0046 0.0080 |

0.0009 0.0023 0.0040 |

| 0.5 0.5 0.5 |

50 72 86 |

8 8 8 |

0.0182 0.0743 |

0.0091 0.0219 0.0372 |

| 0.5 0.5 0.5 |

50 72 86 |

8.6 8.6 8.6 |

0.0688 0.1541 0.2422 |

0.0344 0.0771 0.1211 |

To use the chart, multiply the conversion factor closest to the combination of pH and temperature by your measured TAN. This will yield a rough estimate of UIA. Remember that toxic levels of UIA are anything above 0.05mg/l, so a combination of Total Ammonia Nitrogen (NH3/NH4) of 1.0mg/dl at a temperature of 72 and a pH of 8.6 would have an estimated NH3 concentration of 0.1541mg/l, easily enough to stress and possibly kill a pond full of koi.

Low temperatures are protective, but the ability to separate out toxic from non-toxic nitrogen levels as the pond warms up can head off trouble.

©2006 Robert D. Passovoy, MD

O Noes! More Salts!

Salt? Again? Do we use it or not, and if we do, what for? What we think about salt in our ponds changes as we talk to different experts in the field of aquaculture, and some of the finest arguments I’ve gotten into lately seem to have salt at their origins. There is no question that the versatile compound of a poisonous gas and a toxic and explosive metal has a place in the management of our ponds, and it is time once again to review its current place in our ponds.

A healthy koi does not need salt. Neither does a healthy pond. Koi are carp and carp are fresh-water fish. Their physiology allows them to pump free water out of their tissues back into their environment and maintain very much the same tissue concentrations of salt and water that all living creatures on this planet enjoy. To do this, they expend energy, and being cold-blooded and dependent on the water temperature around them to determine how fast their metabolism turns over, that energy budget is limited. That being said, salt has been shown to be helpful in the management of stressed and injured fish, presumably by lessening the osmotic difference between the inside of the fish and the outside environment, allowing the fish to clear more free water with less energy expenditure. This may allow more of the available energy to be devoted to the koi’s immune response to infection or parasitic infestation, or to devote to wound healing. Ulcers may also be helped with salt, since they represent a hole in the barrier between the inside and outside of the fish. A healthy koi uses its skin, scales and slime coat to keep free water out, and that protection is lost when an ulcer forms. Salt in the water reduces the free water diffusing through the ulcer and in turn reduces the amount of water the fish has to pump back out.

How much to use is open to argument, and you’ll get a different answer from every expert you talk to. The numbers you hear the most range from 0.15 to 0.3 per cent salt, with some advisors going as high as 0.6 per- cent in isolation tanks for very sick fish. Concentrations as high as 2 lb of salt in 10 gallons of water are frequently used as a dip to terminally discourage parasites.

An extensive online search on the subject proved interesting. Google Scholar yielded 133,000 articles incorporating pond and salt. None of them were in any way related to backyard koi ponds and most of them dealt with construction and maintenance of power-generation from non-convecting salt ponds. Narrowing down to keywords “Koi, salt” got me 22,000 articles, only one or two on subject. Those from actual scientists dealt mostly with using high-concentration salt baths as a dip or disinfectant. The only mentions of salt use in ponds fell into three categories. The first set dated from my last search about three years ago and centered around a series of articles by Brett Fogle, who runs MacArthur Water Gardens, an online commercial operation that sells (you guessed!) pond salt. He was all for constant and consistent use. Interestingly, newer articles and posts from him have changed their tone, and he’s a lot less enthusiastic about it now. The second set represented the majority opinion in the articles, posts and blogs that I sampled. Salt is useful as an anti-parasitic dip and an early spring treatment for protection against high nitrite levels. It is NOT recommended for constant treatment in the pond. The third set recommended avoidance of the chemical entirely, except as a high-concentration dip for transported fish, or fish fresh out of the mud pond, the sudden osmotic stress serving to explode most of the parasitic load on a fish on contact. It was interesting to note that the geographical locations of these sources were generally places that did not experience winter.

Salt’s ability to kill parasites is problematic. Epistylis, Trichodina and Ichyophthirius (Ich) will be inhibited (but not eradicated) at concentrations of 0.3% and this effect is often temporary. Fish with leeches, Anchor worms and Costia require individual dipping in 2% salt baths as well as 0.3% concentrations in the pond water, though repeated or extended exposure to salt tends to generate tolerance and resistance to treatment. Dactylogyrus and Gyrodactylus (gill and skin flukes) laugh at salt (a sniggering Dactylogyrus is a nasty thing indeed) and many of the effective treatments require low or zero salt concentrations to limit toxicity.

There is no question in anybody’s mind that salt is vital in early spring. As the populations of nitrifying bacteria wake up and start the conversion of ammonia to nitrite to nitrate, it rapidly becomes clear that the crew that handles ammonia-to-nitrite are the cheerful early risers, while the nitrite-to-nitrate gang seems to need several cups of strong coffee and a couple of extra weeks to get going. During that high-risk period, salt provides protective chloride ion to compete with the nitrite in the fish’s blood. The necessary 30:1 ratio of chloride to nitrite is easily supplied by a 0.2% salt concentration, maintained until nitrite levels drop to zero.

Frequent water changes and very limited feeding will help keep the problem under control.

Okay. If you are going to use salt, it is critically important that you know how to manage it. There are RULES.

Rule 1: Salt in your pond is there forever. If you have evaporative losses, the concentration goes up. The only way to get rid of it is to do water changes. Many, many water changes.

Rule 2: Salt kills plants. Sometimes this is a good thing. Salt in the pond in early spring can limit algae blooms, although it won’t eliminate them entirely. Concentrations higher than 0.2% will wipe out your tender aquatics and keep your water lilies from thriving. Watering your garden with salted pond water gets you the Sahara desert.

Rule 3: You must know how much salt you have in your pond. At all times. This means you need a reliable test kit or a meter. These are widely available and will generally report levels in either % or parts per thousand. Any test kit that reports concentrations in “color zones” or wide ranges is not worth the money you paid for it. For reference purposes: 1 ppt = 0.1%

Rule 4: Change salt concentrations SLOWLY. This means both directions. Slow up, slow down. Bring your salt levels up gradually over a period of days to your target. Bring them down over a period of weeks with water changes.

Rule 5: Don’t leave salt in when you don’t need it. ‘Nuff said.

Rule 6: Know how much salt to add before you add it. Hence the formulas.

Rule 7: Use the right salt. 99.9% pure or “Solar Salt” or “Blue Bag” salt. NOT pelletized or water-softener or road/sidewalk salt. Pickling salt is okay but way expensive and is for pickles, not fish. Pond salt or “aquarium salt” from the pet store is a flat ripoff. Iodized salt is expensive, and the iodine will injure gill tissue, just like its near-relative, chlorine (Look two spaces down from Cl in your handy-dandy Pocket Periodic Table). What you need is available from your local Home Despot equivalent for about 4 bucks per 50 lb. bag. It is evaporated sea water and contains other minerals (magnesium, calcium and others) which will act as buffers to stabilize your pond’s pH and will also supply trace minerals essential for koi health.

The “Not Rocket Science” Formulae:

Lb salt to add = (total gallonage of your system/120) multiplied by (desired salt conc. in ppt – current salt concentration in ppt)

For example:

Pond system volume: 4400 gal

Desired salt concentration: 1.5 lbs/100 gal = 1.88 ppt

Current salt concentration = 0.6 ppt

Lbs salt needed = (4400/120) x (1.88 – 0.6)

= 36.666 x 1.28 = 46.99 lbs salt

What is ultra-cool about this formula is that you can mess with it and get a formula to estimate the gallonage of your system. This is where an accurate test kit is critical.

Total gallonage of your system = 120 x Lb salt added / the difference between the salt concentration (in ppt) before and after you added the salt

To use the formula, you need to measure the salt concentration before and after you add a known amount of salt. Remember to give the salt enough time to thoroughly disperse throughout your pond. One day is just dandy. The amount of salt you choose to add will depend on the size of your pond and the accuracy of your test kit.

For example: A new pond. Medium to kinda big size. Good salinity meter from Aquatic Eco-Systems.

Starting salt concentration: 0.2 ppt

You add: 40 lb salt

Wait one day.

Final salt concentration: 1.0 ppt

1.0 – 0.2 = 0.8 ppt

Total gallonage = 120 x 40 / 0.8 = 6000 gallons

“Not Rocket Science”: Defined as the amount of math I can do without having to take off my shoes and socks.

So, here’s my recommendations:

Use salt sparingly, just like you would any other pond additive.

Monitor levels carefully. Don’t dose too high or change too fast.

Leave it in long enough to achieve your goal, then get rid of it with water changes.

© 2013 Robert D. Passovoy, MD

A Koi Show Manual-Norm Meck Revisited

Download this article as a PDF

The ultimate goal of a water quality team at a Koi show is to return the exhibited fish to their owners in as close to the condition they were in when they were delivered. Without the advantages of some of the sophisticated “flow through” systems in use in the Pacific Northwest, made possible by cell venues that have not only excellent water supply but also extraordinarily convenient drainage, those of us here in the Midwest are thrown back on the system originally developed by Norm Meck for his spectacular shows in San Diego. The main reference for his techniques are outlined in his article January/February 1998 issue of Koi USA. Shortly after the publication of this article, Anne and I went out to San Diego and joined Norm’s water quality team. This was almost the last Japanese-style koi show held in the United States. Shortly afterward, KHV devastated the Hofstra Koi show and effectively put an end to Japanese-style shows. Norm’s article deals with the Japanese show and, to my knowledge, there have been no updates since.

This article will take the reader through the sequence of events leading up to a British-style show, then through the show prep, load-in and maintenance, all the way to check-out and delivery of the fish back to their owners.

Six months and counting:

Yeah, I know it’s freezing out there, but now is when you need to start making lists and getting your materials together. If you have decided to get a Show sponsor to help with expenses, now is when you need to be calling them. There are a load of other shows out there, and only a limited number of vendors with the resources and willingness to sponsor. Get on the computer, fire up the email and get going. If you do it right, your major chemical expenses can be next to nothing.

Go back over the records from the previous year and decide if what you had to work with was enough. Make the adjustments you need, always working with your Show Chairman, so there are no surprises. It is no fun to show up and see ten additional vats that you hadn’t planned for awaiting your attention. Don’t ask what overnight shipping on ten pounds of ClorAm-X costs. Fedex will love you. Your budget will not.

You will need:

- Enough Stress-X (or equivalent) to supply ½ cc per gallon for every vat you treat

- Enough powdered ClorAm-X (or equivalent) to treat every vat initially for 2 ppm “cushion” and additional 1 ppm doses as needed to handle the ammonia produced through the show by the fish. Depending on loading, stress levels and length of pre-show fasting, this can range from zero for a lightly loaded vat to as much as an additional 4-5 ppm for a crowded vat containing Moby Koi and her mother, Kong.

- Enough fresh salicylate-type ammonia test reagents to take you through the show. Order these to arrive 2-3 months before showtime. Use whichever brand you are most comfortable with. Mydor makes a nice, fast 2-step kit, but it has a limited shelf-life. I like LaMotte. It’s a three-step process and is a little slow, but the major vendor (Aquatic Eco-Systems) tracks the lot numbers and can give you the date of manufacture if you call them.

- Ammonia standard. You can make up your own if you can get ahold of dry ammonium chloride and a micrometer balance and do the math and… I get a standard solution of 150 mg/L ammonia from Hach in Loveland, CO. It has a five-year shelf-life and is much easier to deal with.

- A gallon jug of distilled water for rinsing tubes and pipettes, and for making up your ammoniastandard.

- Test tubes, pipettes, graduated cylinders, buckets, tube racks, disposable cups, pitchers,dishwash detergent, paper towels, markers, note pads, scales and whatever else you’ll need to doyour job.

- Your record book with enough vat spreadsheets to match the number of vats you are managing.OR an iPod with Todd Wyder’s nifty new Show Management software (currently indevelopment).

- A battery-powered drill with a beater head from the kitchen clamped into the chuck. This maybe your most important piece of equipment.

- The rest of your pond test kit.

- Your eyes, ears, nose and brain, all in full working order.

Two weeks and counting. . . .

Having gotten the final vat count from your Show Chair, it’s time to pre-measure the chemicals. The goal of the exercise is to prevent any ammonia from touching any fish. To this end, we pre-treat each vat to provide 2 ppm of absorptive power before the fish go in and test with a titration procedure through the show to track the rate at which the cushion is being depleted. Measuring out the doses at the show is impossible. You’ll need to prepare in advance.

You will need:

- The ClorAm-X you got five months ago

- Scales accurate to 0.1 mgm (electronic kitchen scales can do this!)

- Many ziplock sandwich bags

- a good dust mask (you do NOT want to breathe this stuff!)

- A free morning when you can sit outside and do this.

- Plastic cups to hold the bags on the scale

- Boxes to hold the filled bags

ClorAm-X and its new competitor ProAm-X are apparently different enough so nobody seems to be suing anybody else for patent infringement. Interestingly, they both require exactly the same dosing to neutralize the same amount of ammonia. So…

To remove 1 mg/L (1 ppm) of ammonia, 1 gram treats 8.3 gallons.

So: For a 300 gal (6 foot) vat: x grams= 300gal x 1 gram/8.3 gal= 36 grams

For a 500 gal (8 foot) vat: x grams= 500 gal x 1 gram/8.3 gal= 60.2 grams

Wearing your dust mask (you really really don’t want to breathe this stuff) weigh out, seal and store enough 2ppm bags to treat all your vats once, and enough 1ppm bags to treat all your vats 4-5 times. Do this outside on a fairly dry day. The chemical is vigorously deliquescent (look it up) and will weigh more in high humidity the longer it is exposed to the air. You won’t use them all. That’s okay. They’ll keep ’til next time you need them.

Pro-Line has had an exact duplicate of ClorAm-X for years, and it appears to have caught up with them. As of the 2016 season, the new formula smells bad, treats 1/5 less water, is more deliquescent (look it up!) and is more expensive. The smell does dissipate and the fish seem to do okay, but it is more difficult to handle in the prep phase. The numbers are as follows:

6 foot vat @ 300 gallons: 1ppm=45 grams, 3 ppm=135 grams

8 foot vat @ 500 gallons: 1ppm=75 grams, 3ppm=225 grams

If you choose to use this product, you’ll need to order 1/5 more than you were planning on.

Given the ammonia preload given us by our friends at the Metropolitan Water Reclamation Department of Metro Chicago, which ranges from 0.5ppm on a good day and up to 1ppm on a bad day, we’ve started preloading our vats @ 3ppm.

Thursday before the show:

The vats got filled yesterday. The water mopes used a sneaky device invented by Norm’s wife; a length of PVC pipe marked in 1-inch gradations. Each inch corresponds to the number of gallons in that

section of the cylinder. There are two formulas for this: Norm’s quick-and-dirty estimate, which we mostly use and which slightly overestimates the volume, or the actual math, which corresponds to SCIENCE.

Norm’s Quick-and-dirty: Diameter of the vat squared/2

6 ft vat = 6 x 6/2 = 18 gal/inch

8 ft vat = 8 x 8/2 = 32 gal/inch

The only reason this works is that the vats aren’t perfect cylinders. They bulge, and the extra volume in the bulges makes up for the short measure on the stick.

Real math: pi x radius squared x depth (one inch or .08333333 ft) x 7.45 gal/cu. ft. water

6 ft vat = 3.14 x 9 x 0.083 x 7.45 = 17.63 gal/inch

8 ft vat = 3.14 x 16 x 0.083 x 7.45 = 31.33 gal/inch

Ann Meck put t-pieces on either end of the pipe so it could be used to whap out the edges of the vats for filling. One end for 6 foot, the other for 8 foot. A marvelous tool. Go make yourself a bunch!

On arrival at the show venue, set up your gear first. Make sure you have everything you’ll need, where you need it. Then start with the vats. Bully the Show Chair into giving you at least one 6-foot vat for your use alone. No fish will ever see the inside of that vat. It will serve as your source of water for the dosing procedures during the course of the show. Keep it netted. It is yours. Get a sample from it, untreated and fresh from the source. Label it “Source water” and test it for ammonia, along with pH, alkalinity, chloramine, chlorine and pH. Get a water temperature while you are at it. You may get a nasty shock when you do. Make up an information sheet with these values and give them to everybody who has anything to do with fish, ESPECIALLY THE VENDORS!

As part of the preparation for the 2013 MPKS koi show, we pre-treated the show vats with the 2 ppm (AmQuel/ClorAm-X/ProAm-X) ammonia “cushion” recommended in the article published in the inaugural issue of Koi Keeper. As we proceeded with our routine pre-show testing, we noticed that our test runs in multiple unpopulated vats were “breaking” at tube 4, indicating that at least 1.0 ppm of our ammonia cushion was gone before any actual fish hit the water.

The water quality team discussed this and developed two hypotheses to explore:

- The water treatment we used (ProAm‐X from Pro Line) may not be binding the ammonia “instantly” asit claimed on the label and our results may reflect an inadequate “dwell time” prior to testing.

- Water treatment at the hydrant source (Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago)includes chloramine (NH4‐Cl) which preloads our source water with ammonia.

To test this, we tested source water for chloramine, finding at least 1.0 ppm of this compound in the source water. We collected samples from a random, untenanted vat and allowed the ammonia standard to dwell for 5 and 10 minutes. The results were the same in both runs, with the “break” consistently occurring at tube 3 or 4. Adding an additional 1 ppm cushion to the vat resulted in a slight break at tube 5.

This year (2014), we tested the untreated water for chlorine (0.8 ppm), chloramine (1.5 ppm). And,

using the salicylate method ammonia test kit from LaMotte, ammonia. Not surprisingly, we obtained a value of 1.5 ppm from this test.

The conclusion to be drawn here is that water pretreatment with chloramine at the municipal water source constitutes a significant pre-show ammonia load and must be measured and accounted for in your show preparation. Your vendors must also be notified of this preload so that they can pre-treat their vats appropriately and avoid losses to their stock.

Chloramine levels can vary significantly from year to year and from day to day, based on water temperature and organic load in the source water.

Two six-foot vats will be reserved for net and bowl (and hand!) disinfection. Bleach (which must be renewed each day) or benzalkonium chloride can be used as disinfectant. BK is easier on skin and is stable, but is way more expensive.

Bleach is effective at about 200ppm, or about 5 oz per 10 gallons water. This averages out to 1 gallon in 250 gallons water, renewed on each day of the show that nets and bowls are in use. This vat is clearly labeled : BLEACH!!!!. The second vat contains sodium thiosulfate at a concentration of 1 gram/10 L water (12 oz per 1000 gal or… well you do the math. You’ve got one of Ann Meck’s tools, dontcha?). This vat is labeled: RINSE!!!!!!.

If you are feeling wealthy, benzalkonium chloride (BZK) is easier on the skin and gear, is relatively koi-safe and does not have to be “boosted” every day. The rinse vat is water only. It is available in solutions of 50% strength from nationalfishpharm.com, (about $125.00 a gallon or $21 per pint). A concentration of 1000ppm is recommended for rapid disinfection. This works out to 1800cc or 60 oz (about 2 quarts) in 300 gallons water. A gallon should last you 2 shows.

Better yet, housekeeping supply companies sell “Lysol No-Rinse” disinfectant in gallon jugs for not very much money. It is a 10% solution of-you guessed it-benzalkonium chloride! 1 gallon added to 512 gallons of water makes up the 200 ppm solution we need. This concentration will disinfect a net or vat or pair of hands with about 1 minute of soaking. It’s soapy stuff. Add it to water, not the other way around. Rinse in water. Label your vats.

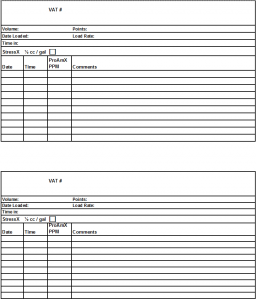

Vat Prep

By now, the vats should all be numbered. Make up a record for each vat, using the form on the penultimate page of this article. Take a 8-12 oz. sample from your source/reserve vat, label it “source water” and set it aside. Each vat is now pre-treated with ½ cc/gallon of Stress-X (or Novaqua), followed by 2ppm of ClorAm-X (ProAm-X). The liquid Stress-X goes in first and is recorded on each form as it goes in, along with the time and date. The powdered material must be dissolved prior to dosing, and here’s where that pitcher and power drill with the egg-beater comes in. Since there are no fish in residence, the isolation procedures you’ll use for the rest of the show aren’t necessary here. Dip out a half-pitcher of water from each vat, dump the powder into the pitcher and mix it thoroughly before dumping it back into the vat. Record this in the “Amq” (Amquel) column as “2ppm” next to your “Nova” entry as you do it. This prevents double dosing or missed vats. Collect a 12 oz sample of treated water from any vat (you treated your source vat, too!), Set it aside.

Using the form on the last page of this article, run and record the indicated tests on your untreated

source water and your vat standard. There will probably be some chlorine and/or chloramine in the untreated water unless your show is running off well water. It should not be present in the treated vat standard. There should be NO AMMONIA ANYWHERE.

Check to make sure that the air system is working well, do your dishes and call it a day.

Friday:

Start EARLY!

Your first task is to prepare your ammonia standard. The goal is to provide a single drop of standard that will create a concentration of ammonia of 0.25ppm in 5cc of distilled water. Since the surface tension of water and the force of gravity don’t vary much, most dropper bottles deliver a drop of a size such that 115 drops equals 5cc. If you can find a bottle that comes close to this, you are good to go. I found an excellent specimen in the 60 cc capacity bottle that contains the #1 Saliclyate reagent for the LaMotte Salicylate ammonia test kit. We tested this bottle repeatedly under show conditions, and it came out at 115 drops per 5 cc each time.

Given the above drop size, you’ll need 50cc of standard solution at a concentration of 29ppm.

Here’s how you get there. The math is real. We got Pat McCray to take off his backward gimmee-hat in order to generate these elegant numbers:

If your head has not yet exploded from the math, you now have your ammonia standard. Label the bottle with the exact directions for making up the standard so you NEVER HAVE TO DO THE MATH AGAIN! Now it’s time to test the standard and your ammonia test kit.

Set up 5 test tubes in one of your racks with 5cc each distilled water. In each successive tube place 0,1,2,4 and 8 drops (0,0.25,0.5,1.0 and 2.0ppm) of ammonia standard. The zero tube is always “tube 1”. The 2ppm tube is always “tube 5”. Mix. Run your ammonia test, mixing between steps. Compare with the test comparator for accuracy. If you don’t have a nice rainbow, either your standard or your test kit is bad. A full line of zero ammonia indicates a failed test kit. Other abnormalities, such as 4+ ammonia everywhere, suggests that you goofed up the prep on the standard.

At the same time, get a sample from any one of the empty vats, or from your vat standard. Set up 5 tubes containing 5 cc each. In each successive tube place 0,2,4,6 and 8 drops (0,0.5,1.0,1.5 and 2.0ppm) ammonia standard. The zero tube is always “tube 1”. The 2ppm tube is always “tube 5”. Mix. Run your ammonia test, mixing between steps. This tests your vat’s protective cushion against ammonia. You should not see any color change in any tube except possibly tube 5. This reflects a 2ppm ammonia safety margin. Remember to use the first set of tests you did with the distilled water as your comparison standard. It’ll be more accurate than the cards or slides that came with your kit.

You will be using this last titration technique over the course of the show to monitor conditions in the show vats. You will be loading a set of 5 tubes with a water sample taken from a vat with fish in it. Each vat that you test will have a cup or other suitable container labeled clearly with that vat number and it is EXCLUSIVE TO THAT VAT. The sample is taken in such away that only the cup comes in contact with the water to avoid cross-contamination.

Keep the cups at your station, re-use them as needed.

Record Keeping:

This is the central principle of this entire exercise. Anything that happens to any given vat should be recorded on the spreadsheet assigned to it. This includes titration results (specifically the tube “break” number), any chemical added to the vat with time and date, and any unusual occurrence (spawning, flashing, stress, jumping, relocation or other events) . The totals of the ClorAm-X dosing from prior shows allow you to plan for the next one. One member of your team is generally the record keeper. He or she will generally have the best idea of potentially troubled vats based on load ratios and prior dosing.

We sample one or two of the most heavily laden vats, one “mid-range” vat and at least one lightly-loaded vat at the beginning of the show. Further testing is done as needed, based on the circumstances that arise during the show. (Irritability or odd behavior, spawning events with the fish moved to a smaller vat and no longer fasting!, and like that).

What you are looking for is a break in the color along the line of tubes. Any positive test for ammonia in any tube reflects enough ammonia to overcome some of the 2ppm safety margin in the vat water.

THE GOAL IS TO PROVIDE A 1ppm SAFETY MARGIN OF AMMONIA PROTECTION IN ALL TANKS AT ALL TIMES.

Therefore:

Color “breaks” in tube 5 or 4 indicate a safety cushion of 1.5 to 2ppm ammonia. Re-treatment of these vats should not be necessary. Break in tube 3 reflects a 1.0ppm safety margin. This is still good, but if it is obtained at the end-of-day testing, it reflects a “trouble “ vat and it and all similarly and more heavily loaded vats will require supplemental treatment to restore the 2ppm “cushion”. Color breaks in tube 2 will need more aggressive repletion. You should never see ammonia in tube 1. That is a vat that has chewed its way through 2ppm of protection and there is now ammonia in with the fish. The professional term for this is “BAD JUJU”. The vat needs to be inspected for evidence of spawning, failure to fast, or simply overloading. The fish should be relocated if possible.

About the most maddening thing in the world is to be in the middle of a titration run, concentrating on your drop count, when someone comes up to your station and starts asking you questions, yelling out numbers and otherwise distracting you from your task. Prepare signage for your table indicating an immediate and ghastly demise for anyone breaking your concentration. Mine says”DO NOT SPEAK TO THE GEEK when he is counting”.The back side of the sign has short-cut charts for the titrations. Make yourself one of these, or more.

The Guests Arrive. . . .

By this time, the fish will be arriving and will be assigned to their vats, floated, benched and entered. Optimal vat loads, maximum vat loads, point scoring and load rate calculation are available on the form on the last page of this article. These values have been arrived at on the basis of a wide base of show experience at multiple shows. It seems to work better than prior estimates of vat loading from previous articles. The load ratio is a useful tool to identify those vats that are likely to use up their safety margin most rapidly, and provide a bellwether effect for similarly loaded vats. Your show staff should provide you with the number and sizes of fish in each vat. Since shows all conform to the “British Style”, no fish will be moved from its vat unless a vat is being broken down due to unusual circumstances.

As the data comes in, survey the vats, determine the load and calculate and record the load ratio for each vat. Pick out one or two heavily loaded vats, one or two mid-range and one lightly-loaded vat as your target vats.

As the data comes in, survey the vats, determine the load and calculate and record the load ratio for each vat. To do this, get a report from your benching crew as soon as they have data available and divide the total points in the vat by the OPTIMUM load for that vat. A 6-foot vat has an optimum load of 20, an 8-footer has an optimum load of 35. An optimally loaded vat will have a load ratio of 1.0 or less. Vats with ratios greater than 1.0 will need either closer monitoring, or some of the inhabitants will need to be relocated to another vat. Pick out one or two heavily loaded vats, one or two mid-range and one lightly-loaded vat as your target vats. A show venue data sheet with fish size (1 through 8) and their corresponding point loads appears at the end of this article, along with a specimen vat record.

Be aware of a significant glitch in the benching system! If your show admits longfin koi, they are all benched as a size 7 fish, no matter what size they actually are. This will register in your calculations as a severely overloaded vat, especially if the owner really likes longfins and brought 3 or for of his size 2s. (Yes, it did happen like that at the 2016 MPKS show. I’m asking to get that glitch fixed.)

A lot of what we do here seems concentrated on chemical and mathematical fiddling. If this were just SCIENCE, it’d be boring and nobody would do it. Most of what we do, however, depends on our ability to judge what the conditions in each vat are based on a number of very subjective clues. Once the vats are loaded, it is our responsibility to survey each one fairly frequently, looking at the fish for signs of stress( clamping, flashing, red fins, irritability) and at the water for signs of sloughed slime coat, poor fasting or spawning. Often, our noses are better at this than our eyes. While we’ll be routinely testing our target vats, any vat that looks “funny” will rate a test.

It’s Friday night. The vats are still fresh, everybody’s tucked in and netted. No testing yet, no re-treatment necessary. Go home.

Saturday: SHOWTIME

Get on-site at least two hours before the show opens. Uncover the vats and survey them for problems. Full quarantine procedures apply from this point on. Do not cross-contaminate. If you come in contact with water from any vat, disinfect before you approach another. Get samples in labeled cups from the target vats and set up titration runs on them.

In general, any stretch of time in excess of 8 hours will probably require a 1ppm treatment boost as a routine procedure. Plan on a 1ppm treatment for all vats every morning and at 4:00pm during the show. Additional treatments will be guided by your titrations. The exceptions will be the lightly loaded vats which may need only one or two treatments.

With fish in the vats, re-dosing with ClorAm-X changes technique. Your reserve vat now becomes your best friend. Lay out a 1ppm packet of ClorAm-X by each vat, get that drill and pitcher and a whole lot of buckets. NEVER dump the powdered product directly into the vat. The fish are fasted and hungry, and will swim directly to it and slurp it down. While it is non-toxic when dissolved, in the powdered state it is lethal. Fill your buckets from the reserve tank and fill your pitcher from the buckets. Dissolve the powder in the pitcher with the drill and disperse the solution as broadly as you can into the vat. Record each dose as “1ppm” with the date and time in the “Amq” column.

Now review your titrations. Color breaks in tubes 2 or 3 on Saturday AM indicate stressed vats and the need for increased vigilance and additional treatment. Throughout the day, continue to assess the vats, retesting as seems necessary. Stay out of the Judge’s way. Smile, answer questions, shmooze the vendors. Buy a T-shirt.

Plan on a routine ClorAm-X boost as the show closes at 4:00 PM. Testing of the lightly loaded vats may allow you to exclude them from supplementation.

Net ’em up, shut ’em down. Go to the Awards Dinner. If you are nervous about any of the vats, sneak back in to make sure everything’s okay after the Dinner before you go home. Check the air lines while you’re there.

Sunday: Maintenance and shutdown.

Get in two hours before the show opens-again. Retest your target vats and any others that look like they need it. Re-dose with 1ppm, guided by your titrations. Additional supplements as needed. Record as before.

Start packing up. You’ve been washing out your test tubes as you’ve used them, do a final “mega-wash” and pack them away. Keep an eye on the heaviest loaded vats as the show winds down. At this point, the reserve vat that supplied water for your treatments becomes transport water to get the fish home. Try to ignore the vats where those randy little @#%$$**! spawned last night.

Good job. Go home. Start working on next year’s show.

My thanks to Norm Meck, who got me hooked on this craziness. References are “A Koi Show Water Quality Perspective” by Norm Meck, Koi USA, Jan/Feb 1998 and “Disinfecting Recommendations” by Spike Cover, Koi USA, July/Aug 2003. Thanks go also to Pat McCray, an actual math professor who teaches (shudder) calculus to undergrads at IIT. He looked at my math, got a headache and, after yelling at me for a while, agreed to come up with the actual REAL MATH that you see for the calculations necessary to prepare the ammonia standard. Finally, I gotta thank my water quality team at the 20th Annual MPKS Koi Show. Bob, Pat,Todd, Scot…not survivable without your help.

RDP

SHOW VENUE:________________________________ DATES:________________________

SOURCE WATER:_____________________________

Temp:_____________

DO:_______________

Alk:_______________

pH:_______________

Cl/Cl-NH3:______________

VAT LOADING REFERENCE

Limits:

6 foot (300 gal.):

Optimum: 20 points

Maximum: 25 points

8 foot (500 gal):

Optimum: 35 points

Maximum: 45 points

Load ratio: # points in vat (divided by)

allowable points in vat

Vat loading

| FISH SIZE | POINTS |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0.3 |

| 2 | 1.0 |

| 3 | 2.0 |

| 4 | 5.0 |

| 5 | 8.0 |

| 6 | 12.0 |

| 7 | 18.0 |

| 8 | yikes! |

Snag ’em, Bag ’em and Drag ’em

Even if you don’t regularly participate in the competitive end of our hobby (Judged Koi Shows) it is worthwhile getting the hang of transporting your koi in the safest and least stressful manner. I do mean stress, both on your koi and you as well.

Your own stress levels are judged best by you and your loved ones, but they will not be reduced by elusive and edgy fish, soggy pants and fish sick on arrival. Koi are primitive as metabolisms go, and being “cold-blooded”, have only so much energy to expend on basic needs, such as breathing, osmotic balance and resistance to disease. Any stress (noise, vibration, sudden environmental changes, etc.) will alarm the fish, activating its flight response and expending energy they would normally use for routine maintenance. Transporting your fish can include practically all of the harmful stressors to which it is susceptible. Minimizing them will increase the likelihood that you’ll deliver your livestock to its destination in a condition that will allow it to recover and thrive.

Preparation for the move is key, and should start well before the move. Feeding should stop five days before the event. While this will certainly earn you the “stink-eye” from your fish, the reduction in the amount of ammonia they’ll have to deal with in the bags will result in a healthier and less stressed crittur at the end of the trip. Make sure you have your gear, including bags, nets, rubber bands and boxes laid out before you begin. You do not want to deal with a cranky fish in a net while trying to find the bags or the rubber bands that have inexplicably gone walkabout.

The Snag

Extracting a koi from a pond is a task with a huge number of variables, based roughly on the design and depth of the pond, the number and size of the fish and the size and skill of you and your helpers. Larger koi are less likely to panic, move more slowly than smaller fish and are much more visible in the pond. This makes them much easier to catch. Smaller fish have “Evade” hard-wired into their tiny brains, and are fast, elusive and likely to jump. They are experts at wedging themselves into spaces too small for your net and are often hard to see, especially if your water has been clouded up in your attempts to capture them. For this reason, your larger fish should be your first targets if you are moving several fish. You want them out of the way in your holding area while you and your crew are fresh. The pursuit of the tiny will take up a lot of time and effort, and you may quit in frustration, leaving them in the pond to mock you forever (or until they get too big to hide!).

You will need the following equipment:

- A generous holding area, if the fish are being isolated or held while the pond is cleaned

- Many fish transport bags. These are large, heavy-duty plastic bags designed for fish transport. They are 3 to 4 mils thick and very strong, but not impervious. (If you need some, look in the Aquatic Eco-Systems catalogue, page 209 or aquaticeco.com, search on “transport bags”.) Always “double-bag”. Plastic is not reliable, seams give, pinholes magically appear and the fish arrives in a bag bereft of water, oxygen or both, mostly dead. Double bagging limits the risk and contains the potential damage.

- Oxygen, especially if the fish are traveling a long way, or will be in the bags for longer than an hour or two. Air will do for short trips.

- Big, sturdy boxes. These can hold one or more bags o’ fish. They can be heavy cardboard at one end of the cost spectrum, or be plastic with wheels and handles at the other. They should all have lids or covers.

- Rubber bands. Big, thick ones.

- Old towels, newspaper, foam rubber, whatever.

- Cold packs, especially for summer transport.

- Nets with long, rigid handles, big screens with small mesh.

- Lots of help. Preferably not tanked up on caffeine before the event.

- Seine net. If your pond is large, you’ll need to limit the area available for your fish to hide. Lure your fish to their usual feeding area and block off the area with the seine. It won’t be perfect, but it’ll help.

- A “blue bowl” or other smooth-sided basin large enough to briefly hold your largest fish.

Right. The goal here is to gently chivvy a fish into a bag with the minimum of alarm and stress, get the bag out of the pond, treat it with oxygen and get it into a box as smoothly as possible, with the absolute minimum of splashing, shrieking, swearing and actual direct contact. Station your netters at opposite sides of the pond, select your target, and gently ease your nets into the water. One of your crew should have the bags and maybe a sock net handy. Slowly guide your target fish towards the person with the bags and contain the fish at the surface without actually lifting it out of the water. The best thing to do here is have the transport bags (doubled, right?) partially filled with pond water and ready to slide the fish into. This does mean getting wet, but if all movements are slow and deliberate, it works well, especially with the larger fish.

The smaller the fish, the harder it gets. The trick here is to anticipate its movements and block them with one of the nets. Little koi are great jumpers and capable of fantastic turns of speed. Do not try to keep up with their movements from behind. Even edge-on, water resistance will slow your net movement enough to make the exercise futile. Do not try to catch a fish with sudden net movements (hence the “no caffeine” instruction). Small koi register that as “attack” and take off. Do not give in to the temptation to get in there with them and wrassle them into submission. They are much better designed for the aquatic environment than you are, and it will only give them another opportunity to mock you forever. (See illustration, which depicts the ultimately unsuccessful and embarrassing attempt of past MPKS president Yoshinogo Wakazashi to capture and transport his prize Cha-Goi “Old Honker” to the Third Annual MPKS Koi Show. The rest of the club is up in his living room on the bluff above the pond, watching the debacle, getting drunk, and laughing themselves sick.)

The smaller the fish, the harder it gets. The trick here is to anticipate its movements and block them with one of the nets. Little koi are great jumpers and capable of fantastic turns of speed. Do not try to keep up with their movements from behind. Even edge-on, water resistance will slow your net movement enough to make the exercise futile. Do not try to catch a fish with sudden net movements (hence the “no caffeine” instruction). Small koi register that as “attack” and take off. Do not give in to the temptation to get in there with them and wrassle them into submission. They are much better designed for the aquatic environment than you are, and it will only give them another opportunity to mock you forever. (See illustration, which depicts the ultimately unsuccessful and embarrassing attempt of past MPKS president Yoshinogo Wakazashi to capture and transport his prize Cha-Goi “Old Honker” to the Third Annual MPKS Koi Show. The rest of the club is up in his living room on the bluff above the pond, watching the debacle, getting drunk, and laughing themselves sick.)

If direct placement into the bag isn’t practical or doable, chivvying the fish into a sock net, then into a bag may work better.

The Bag

Once the fish is in the bag, adjust the amount of water to just cover its dorsal fin and allow it to float off the bottom. Expel as much of the air as you can and fill the bag with oxygen. This can be obtained from industrial gas supply companies or welding supply houses. If you do not have oxygen, hold the top of the bag as wide open as you can, then close the neck of the bag rapidly, trapping as much air as you can in the top of the bag. Twist the bag shut and secure it with two strong rubber bands, secured first at the bottom of the twist with a slip loop, then doubling over the twist and wrapping the free end of the loop around the doubled, twisted bag neck. Rubber-band each bag INDIVIDUALLY! All fish should be “double bagged” and all bags should be carefully checked for leaks both before and after loading. This is a great time to carefully inspect your fish for dings, dents, ulcers and other signs of disease and trauma. Some fish will bleed from the gills when transported. This is a sign of stress, and usually is not harmful. Replace as much of the fouled water in the bag as you can with fresh pond water, and then seal the bag.

Larger fish should be packed one to a bag. Small fish will cohabit more easily. The greater the fish density in a bag, the greater the stress and the more likely it is that your fish will suffer injury.

Move the koi into a storage box as soon as you can, padding the bottom with towels, newspaper or foam rubber. Cover the bag with more newspaper or towels and then close the box. If the weather is warm or if the koi will be in the box for a prolonged time, a coolant pack under the bottom towel will help keep the water cool and lessen stress on the fish.

The Drag

Once in the box, it’s time to load. Regardless of the vehicle, koi should be loaded perpendicular to the direction of travel. Sudden starts or stops with the fish aligned parallel to the direction of travel can ram a fish’s nose or tail into the ends of the box, injuring it. Secure the boxes so they do not tip or shift.

Drive nice.

On arrival, the fish should be floated in their bags for a few minutes to allow water temperatures to equalize. You will want to move the fish out of the bags and into their destination area as quickly as possible. Do this with a minimum of water mixing. If you can lift the fish out of the bag with your hands (rings and watches off, please!) or a sock net, this is preferable. Do not allow water from the destination area to mix with the water in the bag, especially if the fish has been in the bag for a prolonged time. Even a fasted fish produces ammonia, and stressed fish produce more. The water in the bag will become contaminated with the fish waste, but the fish will be protected by the gradual decrease in pH caused by the ammonia and other fish waste. The relatively acidic conditions in the bag will ionize the ammonia to less toxic ammonium ion, and the fish is able to tolerate this. Mixing destination water with the contents of the bag corrects the pH upward (alkaline), de-ionizing the ammonium to often lethal levels of ammonia, and your fish dies right in front of you. Not a good outcome.

Discard the bagged water immediately.

You’re there! You’re done!

Congratulations.

Note for Koi Show exhibitors: Every one of our shows is run on the English system. You are assigned a vat and only your fish will be in it. There is NO mixing of fish, and every effort is made to prevent cross-contamination. To this end, we request that you provide your own “blue bowl” (Aquatic Eco-Systems catalogue, page 209 or online, search “Koi Show Bowls) and net. Barring disastrous screw-ups, your fish should be fine to be reintroduced into your pond immediately on arriving home. If you have any doubts about this, please isolate them for at least three weeks in warm water, feeding sparingly before reintroduction. If you buy a fish from a vendor at the Trade Show and enter it in the Koi Show, your fish will be placed in a show vat with other fish from that vendor only. It is our strongest recommendation that these fish be isolated as outlined elsewhere on our site. (See links to KHV and SVC)

Respectfully Submitted,

Bob Passovoy

President

MPKS